Opinion: You’re a Chinese citizen if China says you are.

It is becoming more challenging to walk the second passport tightrope.

There are plenty of wealthy Chinese citizens picking up second passports to make travel easier.

It establishes a haven for their families, particularly in the U.S., Australia, Britain, and Canada.

But there is a hitch: Unlike the other countries above, the People’s Republic of China technically allows its citizens to hold dual citizenship. As a result, many Chinese-born residents have kept from revealing to their home country that they have a second or third passport. They want to maintain their Chinese citizenship, partly because it would make doing business in the giant economy hard.

What Makes Second Passports so Complex?

The complexities of global passport regulations are not something many Canadians think about.

However, migration specialists say they are often on the minds of many of Canada’s 1.7 million ethnic Chinese. Most of them have links to either China or Hong Kong, which in 1997 became part of China.

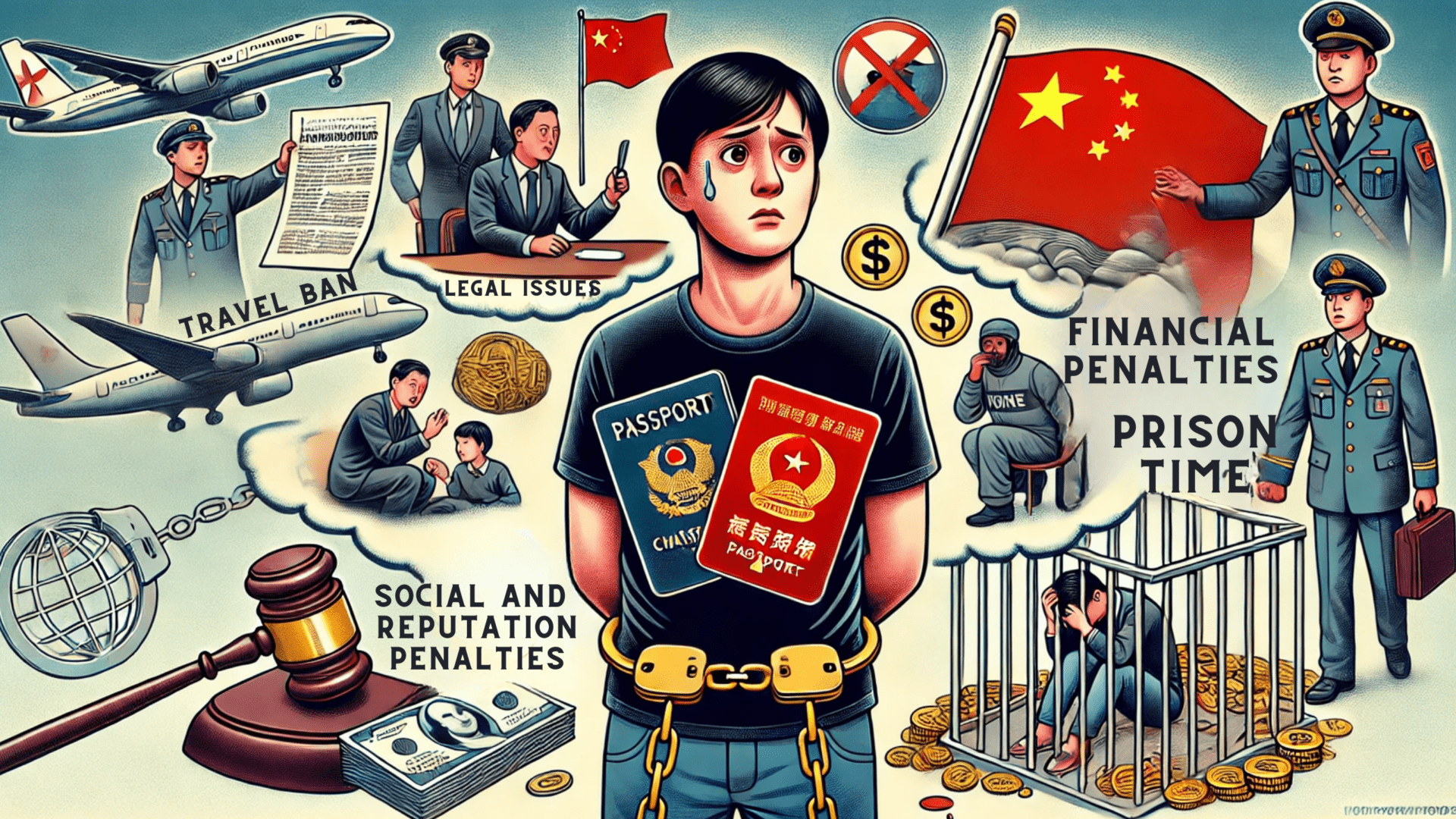

The ramifications of violating China’s passport rules can be devastating. They relate in challenging ways to recent headlines, including Ottawa’s claim last week that it has a plan to airlift more than 300,000 Canadian passport holders out of Hong Kong, Huawei CEO Meng Wanzhou’s ongoing house arrest in Vancouver, and this week’s revelation by the Canadian spy agency that China’s agents are actively intimidating Chinese-Canadians.

Nationalistic China takes the opposite approach to citizenship than laissez-faire Canada. While Canada does little to track whether its passport holders keep a meaningful connection to this country,

China’s authoritarian leaders pressure the 60 million Chinese people spread around the planet to be more loyal. China, which accepts almost no immigrants, claims it’s jacking up enforcement to reign in allegedly corrupt Communist party officials and business leaders.

However, critics say President Xi Jinping is also determined to silence critics and squeeze political rivals. Having more than one passport has become problematic for many Chinese citizens.

You’re a Chinese citizen if China says you are

One poll shows that 47 percent of China’s wealthy want to move to another country. China’s authorities are discovering, including through the Panama Papers leak. Many prominent citizens have been snagging passports from other countries. The consequences for some have been horrifying.

Xiao Jianhua, a Chinese billionaire, went through some hoops to obtain a Canadian passport. He thought Beijing’s security services would protect him. But Xiao was abducted in 2017 from a Hong Kong hotel and taken to China.

What was the Aftermath?

Xiao’s family ran an ad on the front page of a Hong Kong newspaper quoting him, saying, I am under the protection of the Canadian consulate and Hong Kong law, and I enjoy the right of diplomatic protection. But Xiao’s declaration was worthless. Canada could do nothing. He remains incarcerated in an unknown prison in China while the government dismantles his empire.

Then there is Gui Minhai, who left China, his country of birth, to study in Sweden. He earned a Swedish passport. He joined the relatively few who renounced their Chinese citizenship to do the right thing. But then Gui set up a bookshop in Hong Kong, which published gossip about Chinese politicians.

Gui’s capturers caught him in Thailand; four other Hong Kong booksellers disappeared simultaneously. Gui showed up months later at an official Chinese television station, mouthing a forced confession. Although I have Swedish citizenship, I genuinely feel I am still Chinese, he said, urging the Swedish government not to get involved in his case. His sentence put him ten years in jail.

Some Hong Kong legislators have dared the obvious: It doesn’t matter if Hongkongers get new passports because China still regards them as citizens. It’s deeply troubling, said one diplomat, that China deliberately blurs ethnicity and nationality.

Huawei CEO plays a risky game with her passports.

In its extradition request to Canada, the U.S. government maintained that Meng Wanzhou had seven different passports.

But Meng’s lawyers argued she had just two, one from China and one from Hong Kong. However, Meng, whose family owns two Vancouver mansions, had obtained permanent resident status in Canada. Although there is confusion about whether she renounced her residency, it would have given her and her family the right to free education and healthcare. It is also the final step before citizenship.

Since Meng is treated as a hero in China while she fights the U.S. extradition request in the B.C. Supreme Court, how do her country’s leaders deal with the embarrassing reality?

Meng and some of her family members made moves to become Canadian citizens. Immigration lawyers maintain that China turns a blind eye when Communist party favourites take out multiple passports. That certainly seems possible in this case since it is unlikely Meng would ever say goodbye to her Chinese citizenship.

Somewhere along the line, Meng could have done what many other would-be Canadians have done: Renounce her permanent resident status in this country. That would allow her to join the nine million people who have opted for Canada’s popular 10-year multiple-entry visitor visas.

What is the value of a Canadian passport in Hong Kong?

Meng’s case highlights the confusing and crucial differences between Chinese and Hong Kong passports.

Contrary to what many people think, historians such as Jason Wordie maintain China’s authorities consider a Hong Kong passport.

An example is a Special Administrative Region passport, a convenient travel document. So when Canada’s top diplomat in Hong Kong said last week that Ottawa has drawn up plans for a mass evacuation of more than 300,000 Hongkongers who hold Canadian passports, he did not get into the knotty legalities.

Only a fraction of Hong Kong residents’ identities are more closely associated with China than Hong Kong. This could mean anyone born there with a Canadian passport would be on the spot to renounce their Chinese citizenship, however, since China insists on treating Hongkongers as its citizens, especially under the recent crackdown.

If they do so, especially if they shift to another country, they could be treated as foreigners in Hong Kong and China, severely shrinking their prospects.

Many Hong Kong residents with Canadian, British, U.S., or Australian passports often say they remain in China’s booming protectorate because it is far easier to make serious money there. Such people could get around the system by slightly altering their Chinese or foreign-language names in the past.

When they apply for extra passports, it is hard for officials to track how many they have. But China is now perfecting facial recognition technology to catch those who break the rules.

In more ways than one, it’s becoming more burdensome to walk the multi-passport tightrope.